DIRECTOR'S BLOG - A BIRD OF LEACH AND BLAKE

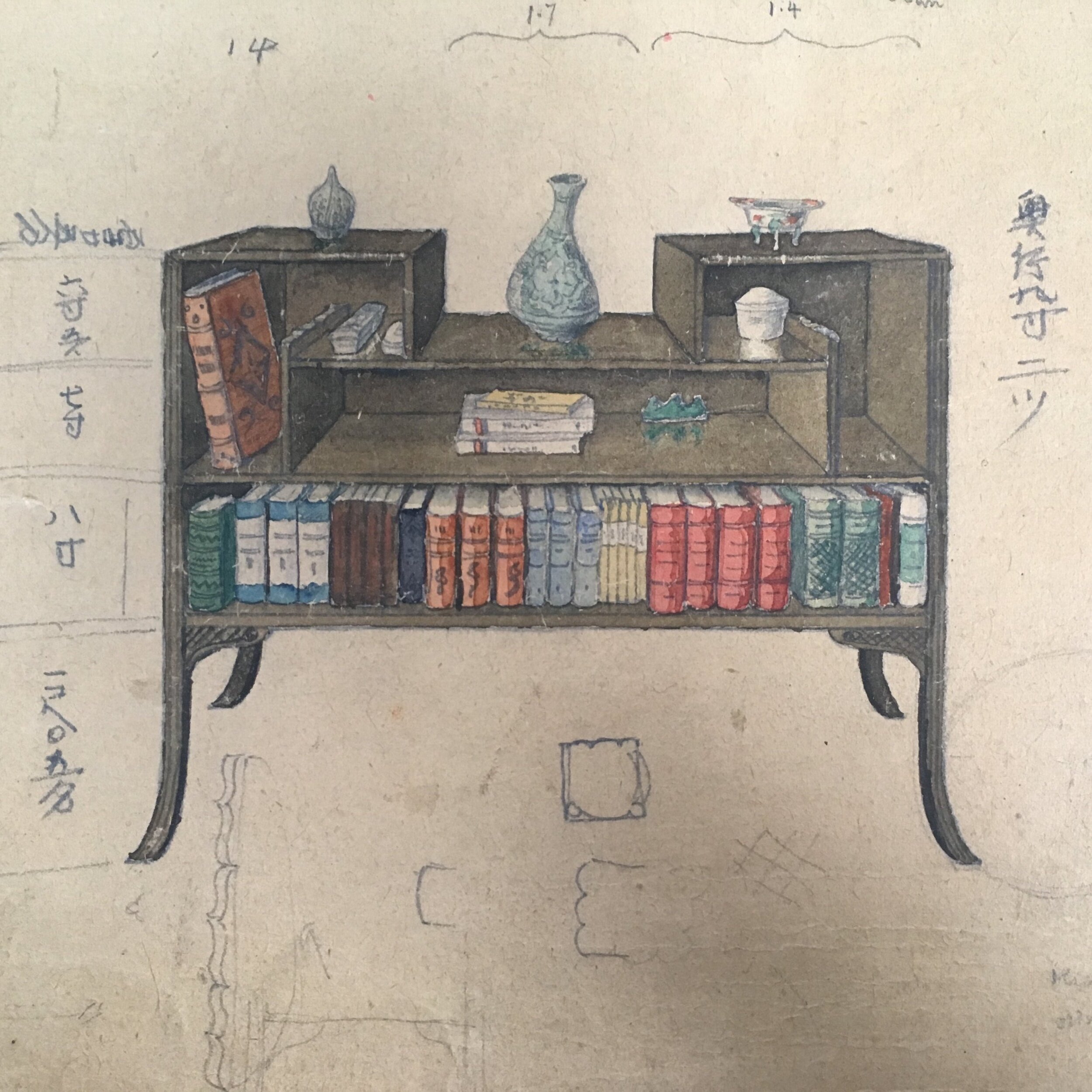

/Bernard Leach’s little raku plate draws together his interests in ceramic history, his reading matter, his ‘philosophising’ and his aspirations as a graphic artist, extolled since he was a child of five or six, by incessant drawing; and by 1917, the year the plate was made, by some ten years as an etcher. Line as well as words are crucial to the plate. Leach drew pots throughout his life: sketches for work that he might make one day; doodles in the margins of a long committee meeting; speedy-yet-alive depictions of ceramics that held his attention, whether a celebrated museum work or a dish seen on his lunch table.

Bernard Leach, dish, raku, slip trailed decoration, 1917, Abiko, Japan. H.4.4cm x d. 20.9 cm.

2021.31 © Courtesy of the Bernard Leach Estate. Photography by Laura Bennetto for the Crafts Study Centre.

The raku plate has a potent back story, for it marks one of Leach’s earliest attempts to produce a form of slipware that acknowledged ceramic history and his topical interests. It is a work of the past and the present. This is touched on by Ian Bennett in his essay for the 1980 Christopher Wood Gallery catalogue. Bennett takes a critical line when referring to Leach’s later and larger slipware chargers. ‘The production of such pieces in the 1920s and 1930s, however beautiful they may have been, is somewhat akin to a talented young painter of today executing brilliant pastiches of “synthetic” Cubist paintings by Picasso and Braque and expecting any art historian to think of them as important contributions to the development of aesthetics! I can think of no piece of slipware by Leach which is not a 17th or 18th century pastiche’.

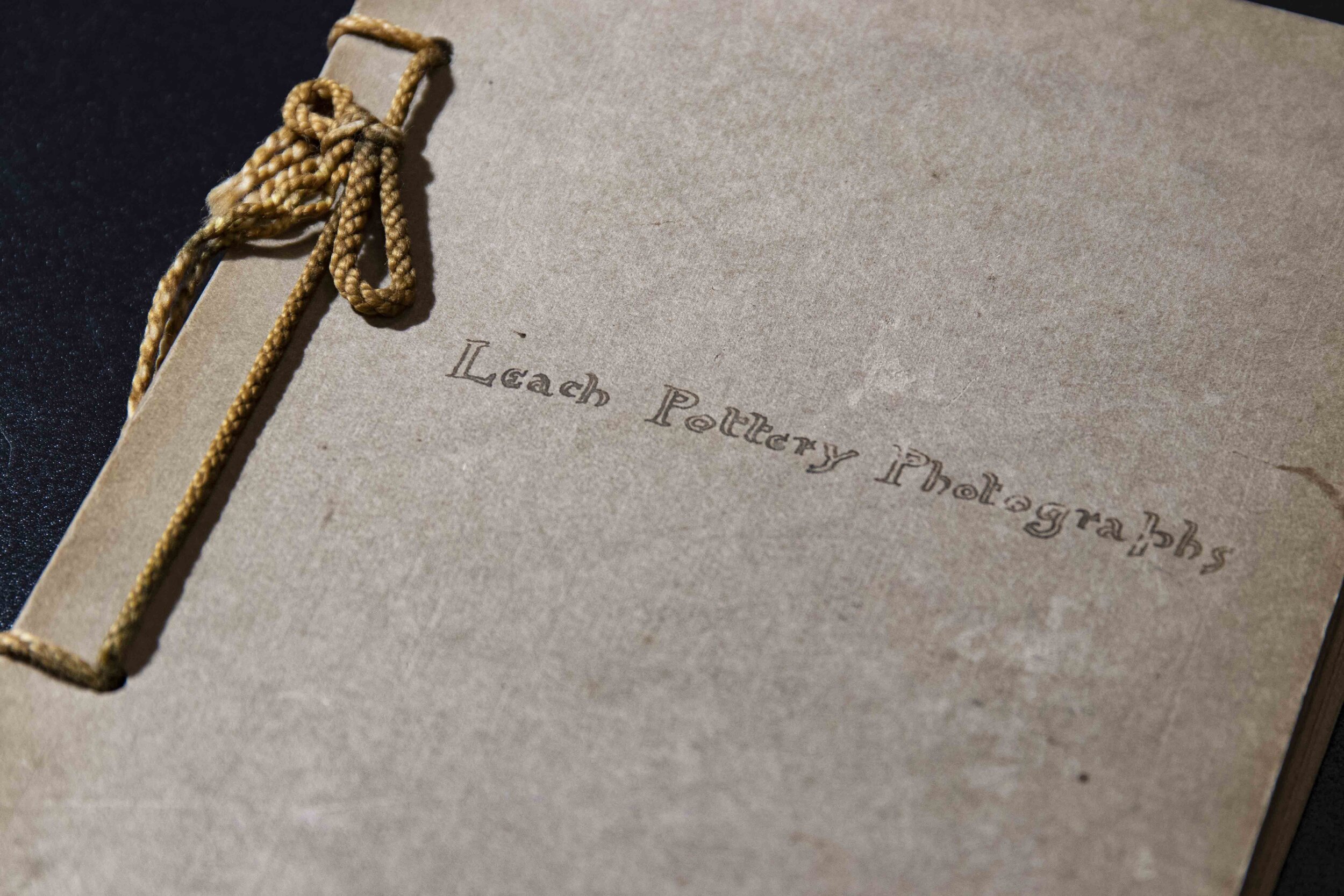

Bennett (who may possibly not have seen this small plate) is alluding here to Leach’s reworking of English Staffordshire slipwares by, for example, Ralph and Thomas Toft, which he knew from his reading in Japan of the book by Charles Lomax, Quaint Old English Pottery. Leach thought about these works for a long time, and he made a lively sketch of a Toft charger as an aid to a book layout, perhaps in the 1950s or 60s.

I think Bennett’s reservations cannot so successfully be levelled at this example. It is one of the very earliest raku slipware dishes that Leach made. His ceramic canvas is tiny, compared with his later, more magisterial, chargers, many of which do indeed relate closely to work by the Tofts. Leach made the smaller plate in his first independent studio at Abiko, Japan, so it is perhaps experimental as well as highly personal. Leach has covered the surface with fluid, even unkempt, imagery and text, as if to load the plate with thought and references, as if to capture the very intensity of first writing the poetry or drawing the line. The bird’s rapid flight catches the startled speed of take-off. It is as if Leach’s mind and hand are in a tumult, and this small space is all he has to encapsulate his expression. The bird is perhaps a dove of peace, perhaps a skylark, perhaps even the precursor to the northern divers or cormorants that fly across his mature ceramic works (and many drawings). It must certainly be the ‘little bird’ in the quotation around the rim from William Blake’s prophetic Book of Urize. It is a bird of Leach and Blake. This reminds us of the poet’s place in the pantheon of Leach and his Japanese friends, artists and philosophers. Soetsu Yanagi, for example, published a massive volume on Blake in 1914, the first such study in Japan, dedicating it to Leach. Perhaps Leach made this plate with Yanagi in mind.

It is a precursive, Japanese-made, English-referenced work. One in which pace, enquiry and reflection are all in flux. These factors seem to me to bring an emotional, introspective charge to the work; and the imagery appears agitated in a way that later slipware drawings do not. It is a rebellion against the good manners of slipware to come. It’s a way of fusing East and West, fusing time (the plate of 1917 could not have been made without reference to those of the 1680s), and perhaps today cannot be seen without the lens of appropriation.

Leach held on to this plate. It formed part of his extensive personal collection of ceramics. It was exhibited in the great retrospective exhibition at the V & A in 1977, marked as a property of ‘the artist’. But by the time Emmanuel Cooper published his biography of Leach, it had disappeared from the public gaze. It is illustrated there in colour, and Cooper says, ‘the design combines a free handling of the motif, cross-hatched pattern and text with a sure sense of composition’. But as to location, he notes, ‘whereabouts unknown’. In fact, we now know that the plate was sitting in upstate New York in John Driscoll’s collection. Janet Leach had inherited the plate on her husband’s death in 1979, and it was eventually sold from Henry Rothschild’s ground-breaking Primavera Gallery in Cambridge.

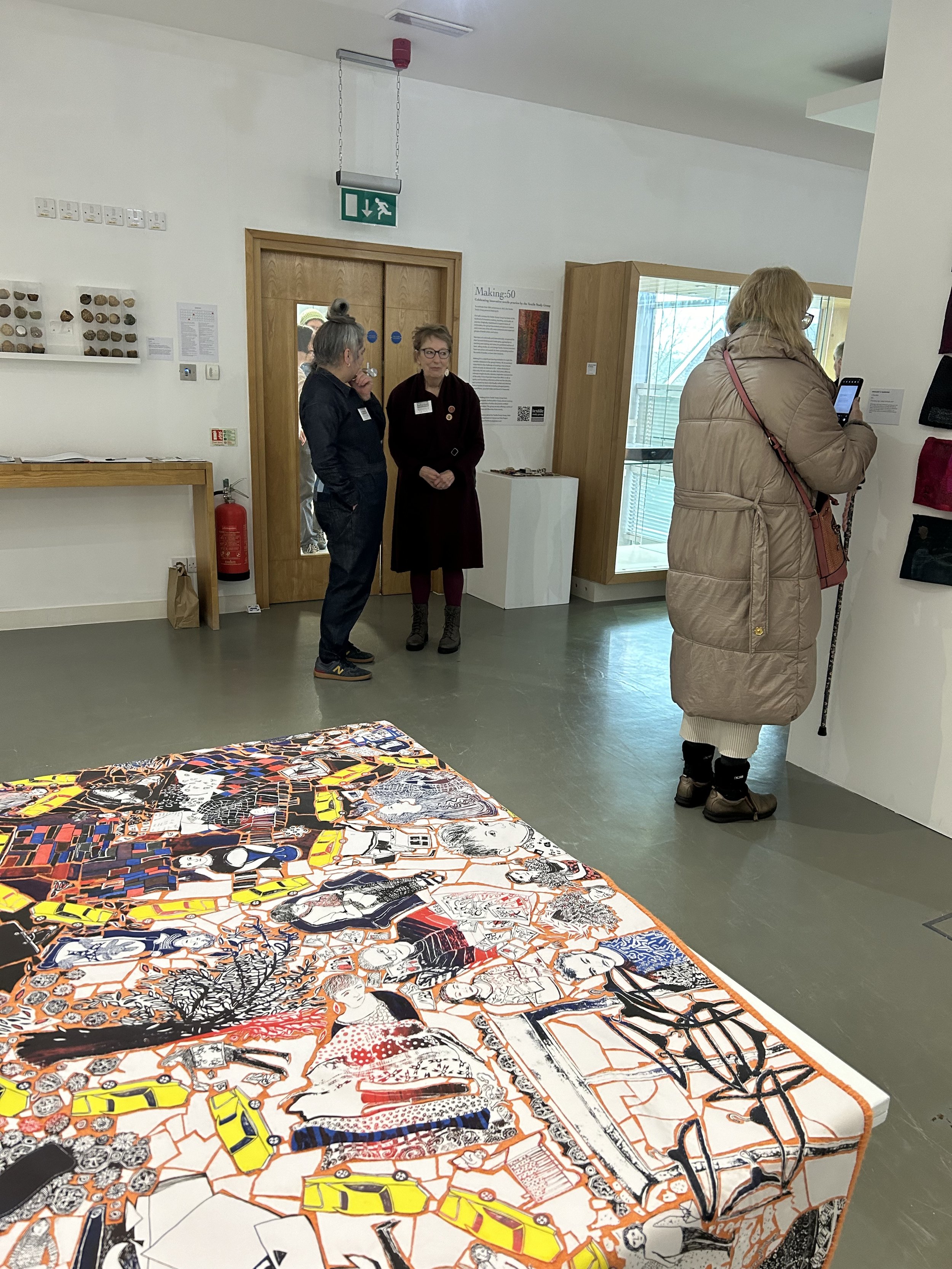

After John Driscoll’s untimely death, his extraordinary collection of British Studio Pottery was sold on 10th November 2021 in the sale ‘The Art of Fire: selections from the Dr John P Driscoll Collection’ held at Phillips, Berkeley Square, London. The Crafts Study Centre was able to bid successfully for the raku dish, and it will be placed alongside other works by Leach (as well as his personal collection of East Asian ceramics) in the exhibition ‘Presence and Absence’ curated by Deirdre Figueiredo with Dr Stephen Knott, from January 2022 onwards.

Purchased with support from the Arts Council England/V & A Purchase Grant Fund and Art Fund

A version of this essay was published in the catalogue for The Art of Fire sale and is reproduced with thanks by permission of Phillips.